How businesses use technology is constantly evolving, and the cyber threat landscape is evolving alongside it. A significant area of growth and risk lies within Operational Technology (OT) and its increased convergence with Information Technology (IT) systems.

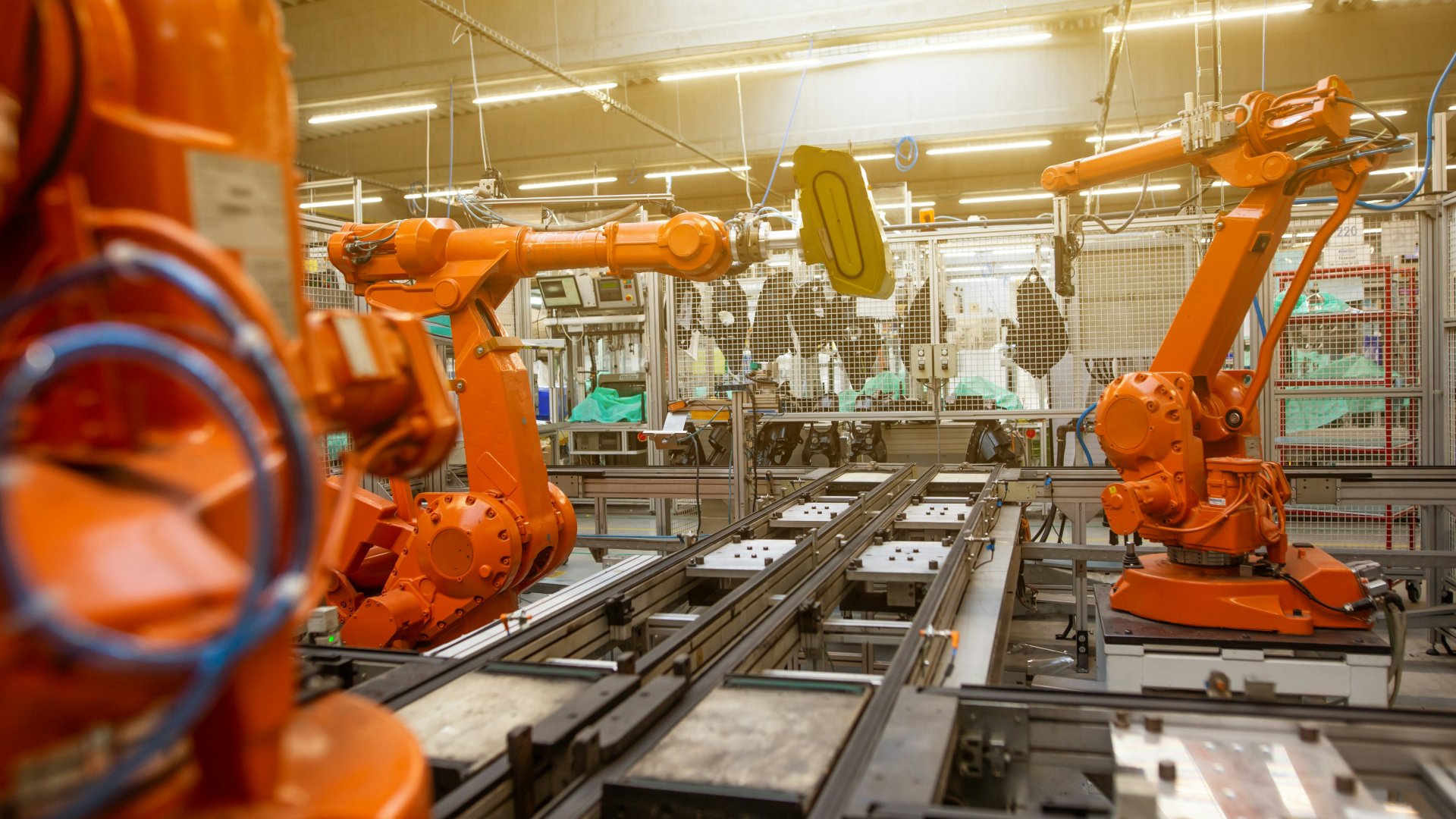

While IT systems typically manage data and communications and represent the devices and applications you would expect to see in an office, OT systems typically control and monitor physical processes, often in industrial environments across different sectors, such as manufacturing or energy. There are more intricate differences between them, but let’s keep things simple for now.

I’ve recently conducted several risk assessments for organisations that use both IT and OT systems, and have found it interesting how the risks change when OT comes into play. In this blog post, I will share some of the lessons I’ve learned and highlight some interesting patterns I’ve noticed, when considering how to conduct an OT risk assessment?

IT vs OT Risks

Some of the ways we traditionally look at IT risks don’t necessarily always apply to OT risks. This requires some flexibility and introduces some unique challenges to the risk assessment process.

More specialised knowledge is sometimes required to understand OT systems and how they communicate with each other and the wider network, making it more challenging to effectively capture which vulnerabilities could be exploited by an attacker and how to mitigate them. For example, OT systems often use software that functions very differently than traditional IT operating systems, and their own set of communication protocols that even experienced IT teams may have never interacted with.

The impact of OT risks also requires a different approach. While the traditional IT framework focuses on the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of systems and data, OT risk assessments must prioritise safety implications, reliability, and the availability of systems and critical process data - there is a strong emphasis on risks that can lead to interruptions in essential industrial processes. For example, picture the compromise of a system that runs an assembly line - if an attacker saw the information stored by the system, this would typically be far less impactful than if they made the system unavailable, causing the assembly line to stop and disrupting the entire manufacturing process that depends on it.

Additionally, while some IT risks can bring about consequences beyond financial losses, OT risks can more often lead to safety impacts due to the industrial processes they are part of, and the essential functions they often provide - if manipulated or made unavailable, this can lead to injury or even loss of life. It can be far more challenging to quantify these safety impacts compared to more traditional ones, especially as they require the organisation to put a value on human life in some cases.

Historically, cyber security has not been a significant focus in many industries that use OT, as OT systems were not originally designed to be connected to the outside world - they typically communicated locally, on a closed network. This isolated them from external threats, and other security controls, such as employee vetting and physical access restrictions, were considered sufficient to protect from internal threats.

However, with the introduction of more connected systems to facilitate reporting on industrial processes and improve efficiency, IT and OT more frequently converge, which has introduced additional risks and required industries to adapt their approach to modern threats. This can be a challenging cultural change that requires organisations to think beyond their local network and consider new avenues of attack, and often creates a technical debt of legacy systems that cannot be upgraded or replaced without significant expense and disruption.

A common architectural approach to mitigate these new risks is the implementation of a Demilitarised Zone (DMZ) between IT and OT networks. A DMZ acts as a buffer, providing a secure intermediary network where data can be exchanged and applications can reside, without granting direct access from the IT network to critical OT systems. This layered defence helps to contain potential breaches and provides an additional control point for monitoring and managing traffic flows between these increasingly interconnected environments.

Given these differences and challenges, it may be tempting to assess OT risks in a bubble, but this is detrimental. To truly understand the risks faced by an organisation, we need to take a holistic approach that considers how IT and OT systems interact across the technical environment.

Interesting Patterns and Examples

There are some interesting patterns I wanted to highlight specifically from my experience that may require additional focus from organisations that use OT.

Knowledge and Documentation Management

I’ve identified multiple examples of key individuals or suppliers holding critical operational knowledge that is not documented, which could be lost unexpectedly. While this is not specifically a security issue, it can have operational and cyber security impacts. This knowledge may be essential to maintaining key systems, especially considering the specialised knowledge often required to understand OT, potentially increasing the impacts of security incidents.

This kind of knowledge should be actively shared with other individuals to eliminate single points of failure, and clearly documented to ensure it is not lost unexpectedly when someone changes roles or a supplier contract is terminated.

Legacy Technology

I’ve raised multiple risks due to the use of unsupported legacy systems. Industrial processes often use hardware and software that was not built with modern technology and the current threat landscape in mind, especially in older estates that have gradually adapted to increased connectivity and data collection. This is partly because specialised OT systems typically have an intended lifespan of around 10 - 20 years, rather than the 3 - 5 years expected for general-purpose IT equipment. Some of these legacy systems contain a high number of unpatchable vulnerabilities that can be tricky to manage. They may also not integrate well with modern security tools, making them more difficult to monitor and apply technical controls to.

These systems may require a flexible approach to risk mitigation, prioritising compensatory controls that minimise connectivity and make it less likely for attackers to reach them. Wider architectural concepts, such as Secure by Design and Zero Trust, should be gradually implemented pragmatically and where feasible. Quantifying the real potential costs to an organisation from associated risks drastically improves understanding of the return on investment of potential upgrades or replacements, which is important as they can be prohibitively expensive and disruptive to carry out.

Supply Chain Risks

I’ve noticed multiple instances of over-reliance on third-party suppliers and insecure remote connections. Since specialised knowledge is often required to maintain critical industrial systems, this can increase reliance on third parties for support, which creates additional opportunities for compromised suppliers and impersonating threat actors to access critical systems. Threat actors increasingly target suppliers as a pathway into their customers’ environments, seeking to leverage trusted relationships to bypass essential security measures.

Supply chain risks can originate in unexpected places. For example, I found that certain systems used by an energy sector customer to manage critical generation equipment had a built-in backdoor that gave the manufacturer access to the systems at any time. Thankfully, in this case the customer had already mitigated this risk through good network security controls before it was identified.

This highlights the importance of documenting all third-party connections, assessing suppliers’ security practices, and considering the risks introduced by third parties, even if more challenging for larger organisations with extensive and potentially opaque supply chains. Strict controls, including Multi-Factor Authentication (MFA), least privilege access, and monitoring should be used for all third party remote connections. Additionally, contractual agreements should be used to ensure that suppliers are operating securely.

IT / OT Convergence

I came across multiple examples of weaknesses in the boundaries between OT and IT environments. As OT systems are increasingly connected to the wider network and external platforms, such as cloud solutions, traditional boundaries and segregation models start to become inadequate. This can create additional opportunities for attackers to access critical OT systems through the IT network, or vice-versa.

For example, I found that an energy sector customer was essentially bypassing their network perimeter security controls by using a third party cloud-hosted system to manage a key industrial process. This system could be accessed from any device and any network by default, using a web interface - if a user’s credentials for the system were compromised, an attacker could use this interface from anywhere in the world to take critical equipment offline.

Without taking into account the broader picture, we can miss critical risks that arise from the way OT and IT systems interact with each other. As more connectivity is introduced to OT environments, organisations need to keep pace and apply a risk-focused approach. Additionally, it’s still important to ensure that IT systems, including those that do not form part of a critical process, are robust and follow modern IT security best practices to reduce their exposure to attacks that could have wider consequences.

Physical Risks

I’ve identified multiple physical risks that had the potential to cause serious disruption to organisations. OT systems are often deployed out in the field, far from corporate offices. Depending on the organisation’s industry, this could be anything from a large factory to a small control room that is little more than an outdoor shed. This can make traditional physical security more difficult to achieve, and increase opportunities for threat actors to physically sabotage critical systems to disrupt operations.

This requires additional considerations when choosing and configuring physical sites that will host critical systems. This may mean choosing sites that require additional motivation to attack, and configuring them to require additional capability or offer less reward for threat actors. Controls that enhance resilience and limit potential consequences are key, especially when physical security is not cost-effective. For example, the compromise of a single control system hosted at a remote site that has few physical security controls should never lead to extensive compromise or interruptions to critical processes.

Conclusion

OT risks often have their own share of inherent challenges that differ from more traditional IT risks, and we need to take a holistic approach to understand how the IT and OT environments interact with each other. As with any good cyber risk assessment, other aspects of the organisation, such as its people and supply chain, should be considered to produce valuable insights.

Although the threats to OT systems are plentiful, and assessing their risks requires additional considerations, there are positive trends as well. Many of the technical teams and business leaders I have worked with have shown a strong commitment to improving their security posture and have evidenced their ability to adapt to the changing threat landscape at a rapid pace, especially over the last few years.

Additionally, UK-wide and industry-specific regulations, such as the Network and Information Systems (NIS) Regulations, are making a real difference for OT security in critical sectors, and the upcoming Cyber Security and Resilience Bill is set to further strengthen this. For companies running essential services like energy and transport, robust cyber security has become a regulatory requirement.

This shift and attention towards protecting critical industrial systems is welcome, promising to create a safer and more resilient industrial environment across the UK. If you’d like help understanding and managing your OT cyber security risks, get in touch.

Photo by Simon Kadula on Unsplash